This article was originally published on www.myHRfuture.com/blog.

Innovation does not just change our behaviour (think of how smart phones and social media have changed how we interact), but also what we need to master to be relevant in the economy. Simply put, the faster we innovate, the faster jobs are redesigned to incorporate new technologies.

The data on this issue suggests that there is a general trend towards more relationship-based and expertise-driven work. However, it also suggests that the type of expertise deployed is also changing more quickly. This results in a shrinking shelf life of technical skills. Our technical knowledge and abilities become less relevant faster. Against this backdrop, organisations and individuals are trying to find ways to stay relevant. It’s a difficult and stressful process that creates a lot of uncertainty.

This is why concepts like ‘growth mindset’ and ‘agile mindset’ have caught the attention of business and HR leaders. Indeed, large and very successful businesses have made them central to their culture and values systems. Leaders know that they need everyone to work even harder to keep up with the changing needs of customers. As the inspirational Satya Nadella has said, “the learn-it-all does better than the know-it-all”. For many people, the idea that having the right mindset is central to learning and change, makes sense.

But does it make sense? Mindsets are belief systems – assumptions, attitudes and opinions – that inform decisions and behaviours. They are vital for building culture and collective coordination and action. When we want a group of people who find it easier to work together to solve a problem, it really helps if they share a mindset. However, the evidence that these belief systems impact learning and change outcomes for individuals in business is mixed. Robust research does suggest that intelligence has improved dramatically over the last 100 years, mostly because of the change in the demands we experience from our environment (e.g. we need to think in more abstract and complex ways, so we learn to do so). People change because they must.

Looking more closely at the way organisations express their needs for a growth or agile mindset, what we often see is that they articulate a set of capabilities and behaviours which help people learn and adapt. What they are really looking for is a set of skills that help people drive continuous learning and change. This is important because it means that adopting an always-on learning approach is much more than a way of thinking – it is also a set of skills that we can teach people.

In our work with the Singapore government, we have been calling these the “skills to build skills” or “critical core skills”. They are the skills that form the foundation of our resilience as a species. They are also skills that endure consistently over time to enhance our technical capabilities.

Introducing the Critical Core Skills

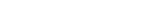

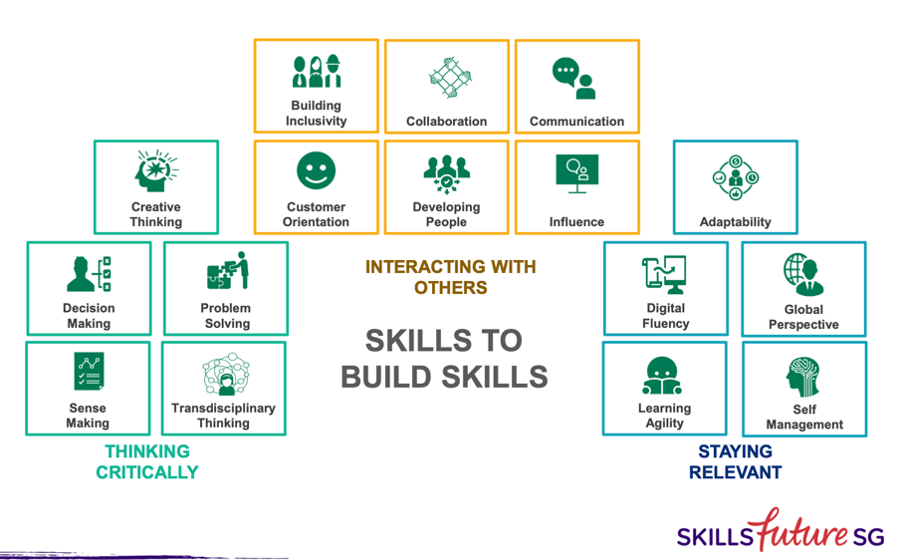

The framework we at Mercer helped to develop for the Singapore government outlines three vital clusters of critical core skills:

- Thinking Critically – These are cognitive skills that are needed to think broadly and creatively in order to see connections and opportunities in the midst of change. Cognitive skills are the root of technical skill development and progression.

- Interacting with Others – Learning from other people is one of the most effective ways to acquire new skills and ideas. Being effective at interacting with others means thinking about the needs of other people, as well as being able to exchange ideas and build a shared understanding of a problem or situation. Increasingly people need to be able to combine their technical skills with those of others to succeed.

- Staying Relevant – Managing oneself effectively and paying close attention to trends impacting work and life provide the strategies, direction and motivation for technical skill development.

We can call these critical core skills “skills to build skills” because they all contribute to consuming, processing and using new information effectively. In other words, these skills are all about learning in some way. Whether people are learning about the needs of others or seeing patterns in the world around them – these skills power personal insight and development.

Three things we learned from building the Critical Core Skills framework

1. Soft skills increase in importance

In our discussions with a cross-section of the organisations in Singapore (c. more than 100 of them), we found that the increase in innovation and use of new technologies had heightened the demand for softer skills like influence, adaptability and sense making. This was, in part, because work has become more complex, but also because it had become more important to effectively interact with other people. Gone are the days when people could get away with being a technical genius who is impossible to work with (like Dr. House). The technology we use exposes us to other people more often – making our capacity for connection more important.

2. People learn most effectively from other people

We also saw evidence that most people at work learn most effectively from other people. The inference was that social and collaborative skills also enhanced learning opportunities (perhaps it should come as no surprise that people who learn to listen and interact well with other people also consume a lot of new information). Indeed the research on humility in leaders suggests that one of the reasons why being humble boosts leadership effectiveness is because it allows a more efficient and open exchange of information between different levels of hierarchy.

Informal, peer-to-peer learning is often not acknowledged as learning within organisations. Collaborative activities like brainstorming and problem solving inevitably involve learning from other people however this is not defined in any way as ‘learning,’ but simply as ‘work.’ The more visible we can make this kind of learning – the more we can acknowledge it as such – the more it can be consciously implemented and enhance work and the quality of work life.

3. The rising importance of self-management

Another striking insight centered around the rising importance of self-management. We noted that many jobs had become less structured over time – especially as technology has changed when, where and how we work. This heightens the importance of being able to manage your day independently and to take responsibility for your own work and personal growth. Indeed, psychologists have long known that highly conscientious people (who often display very effective self-management behaviours due to their personality) tend to be more successful at these things.

What we noted is that it has become even more important for all of us to learn skills and strategies that allow us to self-direct more often. Perhaps individual employees already understand this, which is why the Coursera “learning how to learn” course is the most popular one you can find.

Taking the critical core skills challenge seriously

So how do we get everyone to take the critical core skills challenge more seriously? Let’s start with the recognition that culture and capability are deeply connected. Yes, we absolutely need a mindset and culture that values learning, and (correctly) assumes that human beings have a remarkable capacity for adaptability. However, we also need to recognise that human behaviour is strongly influenced by skills and capabilities. Unless we also strengthen the skills we have the deliver on the promises of a growth mindset, then we will never achieve our full potential.

There are a few ways we can approach this:

- The first is to be the change we want to see. HR teams and business leaders can be very effective role models for learning and skill building – especially when they are open and curious. If influential people in our organisations showcase their approach to building critical core skills, then others are likely to see that as a signal that this sort of learning is important. At IBM, leaders are encouraged to publish figures about the learning hours and badges achieved, to signal to the organisation that the organisation sees the value in investing in skills building. Again, Nadella’s approach to this is also instructive.

- The second is to make sure we are articulating our demand for these critical core skills. In our research we looked at the average number of core skills that companies look for when they post job advertisements online. We found a lot of variance – with organisations in the US looking for about five per job ad, organisations in the UK looking for about three per job ad, and organisations in Asia looking for about two per job ad. We need to make sure we articulate our needs for critical core skills clearly when we create jobs and look for candidates – otherwise how will people know we value them?

- The third is to invest in signalling mechanisms so people can communicate their skills more effectively. How do we know if someone has these skills? All organisations should be looking for mechanisms for people to signal their competence in a variety of areas. Doing this for technical skills is relatively easy as simulation assessments that allow people to demonstrate what they can do are quite common. However we should also pay more attention to the way we use feedback about softer skills (in performance reviews or 360 assessments) to help someone build a non-technical profile too.

- Last, we should all encourage more assessment and feedback, more often. How can we know if we are building skills if we do not check for them? Assessment is often scary for people because it feels deterministic (think of how school exam results impact your future…). But if we approach assessment as a way to drive learning, then it can be a very impactful and effective tool.

Final thoughts

Learning takes effort – which is why there is so much concern about how motivated people are to spend time on it. It is clear that some people have personalities that enable learning. Others are simply privileged to have the resources and time (learning is often a pastime of the elite). Taking a skills lens to this problem provides a different perspective. If we can teach people skills that help them learn more effectively, perhaps the whole process will become more accessible to everyone.